Shoulder Conditions

The Rotator Cuff

-

Scroll Down

Rotator Cuff Repair

Mr. Hannan Mullet

- The Rotator Cuff

- A Patient’s Experience

- How did I injure my Rotator Cuff?

- Treatment options available

- What is the Required Rehabilitation?

- Detailed Anatomy of the shoulder

- Patient Booklet

A Patient’s Experience

Barry was concerned that he may have broken something and went to the urgent care clinic where x-rays were performed which showed no fracture and he was referred to physiotherapy.

Unfortunately, he remained in severe pain and he only regained very little motion and attended his G.P. who was concerned about a rotator cuff tear and referred him to Mr. Mullett.

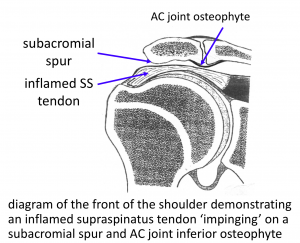

Given the history the team arranged for a special scan, an MRI, which showed a major rotator cuff tear and Mr Mullett saw him for consultation.

By now Barry had significant ongoing pain and even with strong painkillers he found it difficult to sleep. He had very restricted movement and had a very weak rotator cuff. Mr. Mullett showed him the images of the major retracted rotator cuff tear on the MRI scan. *image of MRI shoulder He recommended surgical intervention and Barry was scheduled for surgery within a few weeks.

Mr. Mullett explained that the results of surgery in an acute rotator cuff tear are better if it is not delayed too long. He had keyhole (arthroscopic minimally invasive) surgery to repair the tear and “tidy up” any evidence of impingement which could also be contributing to his pain. Pictures are taken of the shoulder joint during the surgery as a part of his operation records.

Barry stayed on hospital overnight following surgery and the physiotherapist gave him simple exercises to do. He was immediately able to use his arm for simple tasks such as washing his teeth, using his phone and laptop and working from home.

He saw Mr.Mullett at three weeks following surgery and he went through the images from the arthroscopic surgery and was pleased that the wounds have healed nicely.

He gave Barry a detailed prescription for physiotherapy. After 4 weeks he was able to drive again and returned to normal activities around the house . He worked hard at physiotherapy and was able to return to golf after 4 months.

It took a further 2 months for him to return to tennis and in fact took a full year for him to regain his normal service. He was delighted to return to playing veterans league tennis and played a tournament over several days without any problem.

A Patient’s Experience

Barry was concerned that he may have broken something and went to the urgent care clinic where x-rays were performed which showed no fracture and he was referred to physiotherapy.

Unfortunately, he remained in severe pain and he only regained very little motion and attended his G.P. who was concerned about a rotator cuff tear and referred him to Mr. Mullett.

Given the history the team arranged for a special scan, an MRI, which showed a major rotator cuff tear and Mr Mullett saw him for consultation.

By now Barry had significant ongoing pain and even with strong painkillers he found it difficult to sleep. He had very restricted movement and had a very weak rotator cuff. Mr. Mullett showed him the images of the major retracted rotator cuff tear on the MRI scan. *image of MRI shoulder He recommended surgical intervention and Barry was scheduled for surgery within a few weeks.

Mr. Mullett explained that the results of surgery in an acute rotator cuff tear are better if it is not delayed too long. He had keyhole (arthroscopic minimally invasive) surgery to repair the tear and “tidy up” any evidence of impingement which could also be contributing to his pain. Pictures are taken of the shoulder joint during the surgery as a part of his operation records.

Barry stayed on hospital overnight following surgery and the physiotherapist gave him simple exercises to do. He was immediately able to use his arm for simple tasks such as washing his teeth, using his phone and laptop and working from home.

He saw Mr.Mullett at three weeks following surgery and he went through the images from the arthroscopic surgery and was pleased that the wounds have healed nicely.

He gave Barry a detailed prescription for physiotherapy. After 4 weeks he was able to drive again and returned to normal activities around the house . He worked hard at physiotherapy and was able to return to golf after 4 months.

It took a further 2 months for him to return to tennis and in fact took a full year for him to regain his normal service. He was delighted to return to playing veterans league tennis and played a tournament over several days without any problem.

How Did I Injure My Rotator Cuff?

The Supraspinatus Tendon lies over the top of the Humeral Head (Ball) and runs underneath the Acromion (arch of the Scapula).

The action of the Supraspinatus Tendon is to help Elevate and ABduct the arm, it is one of the most heavily used Rotator Cuff tendons and the one that is most prone to wear and tear changes.

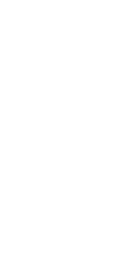

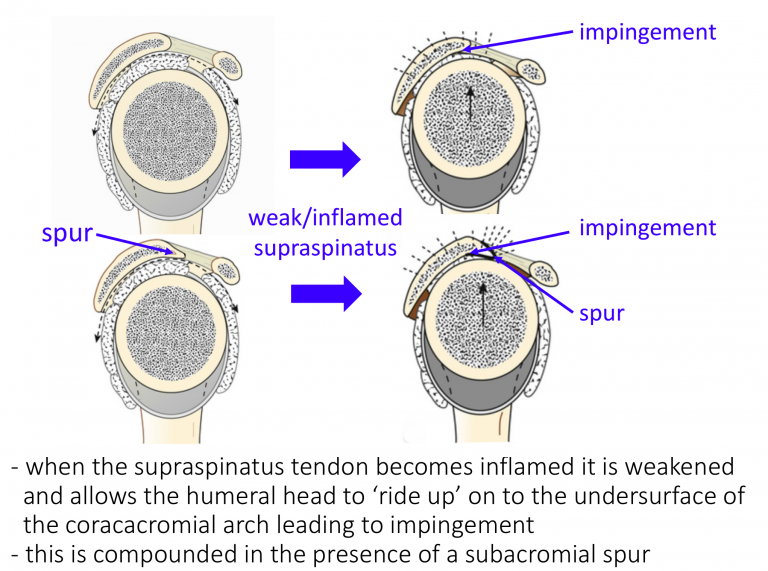

The clearance space for the healthy Supraspinatus Tendon to run underneath the front of the Acromion is usually adequate. However, there is usually not a great amount of reserve space available. As a result, if the Tendon becomes at all inflamed or enlarges, for any reason, it can begin to ‘impinge’ or rub on the undersurface of the Acromion. Supraspinatus Tendonitis and Impingement are inter-changeable names to describe inflammation and swelling of the Supraspinatus Tendon, which usually has a ‘wear and tear’ element.

When the Tendon becomes inflamed it is also weakened which makes it is less effective at pulling the head downwards. These factors can then lead to further damage or inflammation to the Tendon, starting a ‘vicious circle’ of ‘Impingement’.

The shape and angle of inclination of the Acromion can vary between people. Sometimes people refer to a ‘hook’ or ‘spur’ at the front of the Acromion that is related to their Impingement. As a general rule, the shape of someone’s Acromion does not change significantly over time, and it is likely that their Acromion has always been that shape resulting in them having less ‘reserve’ space available for any underlying tendon enlargement.

Acromioclavicular (AC) joint osteoarthritis often develops in patients as they get older. Sometimes an inferior osteophyte from the AC joint can also impinge on the rotator cuff.

There is a small Bursa (fluid filled sac) that lies on top of the Supraspinatus Tendon and beneath the Acromion. Its job is to try and ease the movement of the tendon underneath the bone. This can sometimes get inflamed, along with the tendon, but often has eroded away over time.

Whilst the mechanism of Impingement is a major factor in the development of Supraspinatus Tendonitis, there are a number of other extrinsic and intrinsic factors that can also play a part.

As ‘wear-and-tear’ plays a considerable part in the development of Supraspinatus Tendonitis the onset of symptoms can often be quite insidious. As a result, many people find that their Supraspinatus Tendonitis gradually develops over time. In other cases, a specific injury or incident can aggravate the degenerate tendon and spark off a sudden onset of symptoms.

The early symptoms of Supraspinatus Tendonitis tend to be a background pain over the shoulder with particular discomfort when elevating the shoulder within the ‘Painful Arc’. The shoulder is often uncomfortable to lie on at night. As symptoms deteriorate the shoulder becomes increasingly painful more of the time. Pain tends to occur on more directions of movement and the shoulder can appear to become weaker. Night discomfort often becomes more of a feature. With chronic shoulder pain, the muscles that help to stabilize the scapula often try to hold the shoulder up, in a more protected position. Overtime these muscles can begin to ache so that the pain can appear to radiate up towards the neck and over the shoulder blade.

- History – Most people notice a gradual onset of pain and discomfort over the top and side of their shoulder. Sometimes people can identify a specific injury or incident that triggered their problem. They may notice particular pain on elevating their arm and in bed at night. As the condition deteriorates they may get pain more of the time and on more directions of movement. They also might notice some weakness.

- Examination – Occasionally the patient can experience some discomfort on palpation over the front edge of their Acromion. People may have a ‘painful arc’ on elevating their shoulder and positive ‘impingement signs’. People with Supraspinatus tendonitis often have associated problems with Acromioclavicular Joint (ACjt) arthritis and Long Head of Biceps Tendonitis and may have symptoms and signs of these as well.

- Investigations –

- X-Ray – An x-ray does not usually demonstrate the soft-tissues of the Rotator Cuff. However, the shape of the acromion, ACjt osteoarthritis and calcific deposits can sometimes be noted.

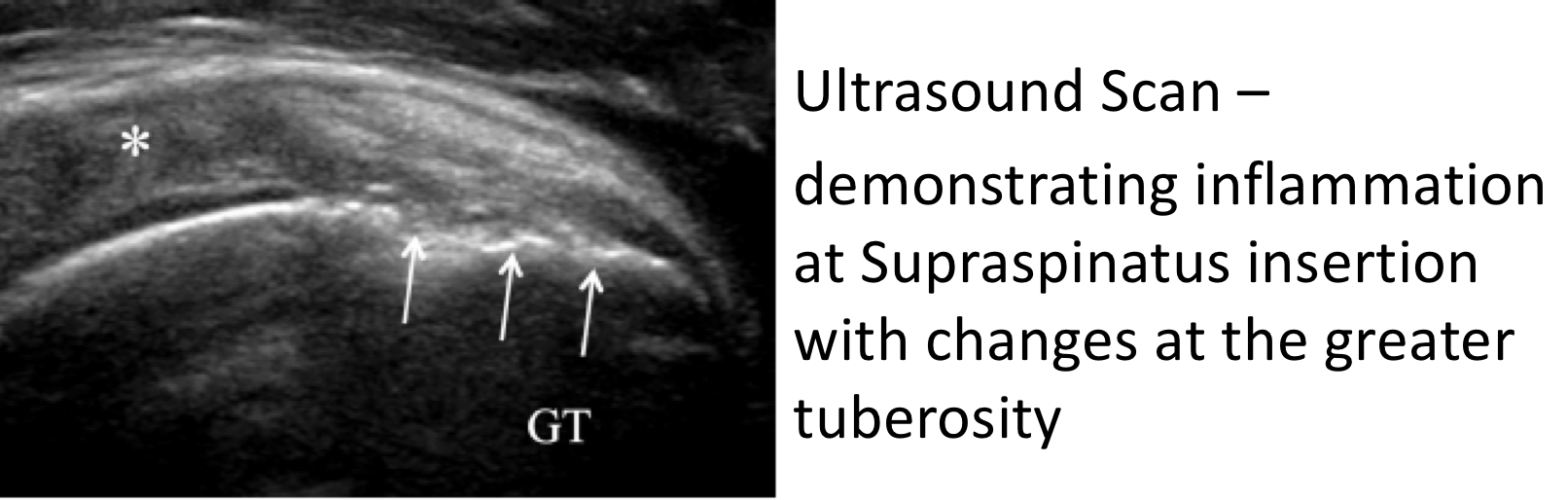

- Ultrasound Scan (USS) – An USS will nicely demonstrate the Rotator Cuff tendons and the Long Head of Biceps. It is able to show whether there is a tendonitis, partial or full thickness tear of the tendons.

- MRI Scan- An MRI scan is the best investigation to visualize the rotator cuff. It can show all of the tendons and whether there is a tendonitis, partial or full thickness tear. It will also demonstrate the acromion and ACjt and their relationship with the tendons. An MRI scan will also show up any other problems around the shoulder.

Rotator Cuff Tears

This refers to a group of tendons that join the muscles that move and support the shoulder to the bone of the upper arm. The tendon is most vulnerable to damage where it is attached to the humerus bone and runs underneath the upper part of the shoulder blade- acromion. Rotator cuff tears are the most common problem in the shoulder and commonly cause pain and restricted range of motion.

Rotator Cuff Tears (Torn Tendon)

- Everyone’s Rotator Cuff Tendons undergo ‘wear-and-tear’ over time. This can lead initially to a Tendonitis, which is an inflammation and fraying of the tendon. Then as the tendons become weakened, it thins out, and can lead to Partial or Complete tears.

- This process is often going on quietly in the background and many people, over time, develop tears without any symptoms and without knowing about it. In an MRI scan study of people over 60 who felt that they had no problems with their shoulder, over 40% had a tear of some size of their Rotator Cuff on their scans!

- However, some people with a Rotator Cuff Tears do develop symptoms. These maybe sparked off by a specific incident or accident, where an acute tear occurs in an already weakened or previously torn tendon. In other people the symptoms may develop slowly representing the progression of a Supraspinatus Tendonitis.

- Regardless of the way that the symptoms of a Rotator Cuff Tear start, when they do occur, they usually require some form of treatment to settle it down.

• The short answer to this is NO

• When the tendon is torn the pull of the muscle will retract the torn edge away from its bone attachment

• The only way the tendon can heal is if it is re-attached

• However not every torn tendon will lead to symptoms and many patients maintain or can regain full shoulder function without requiring a repair

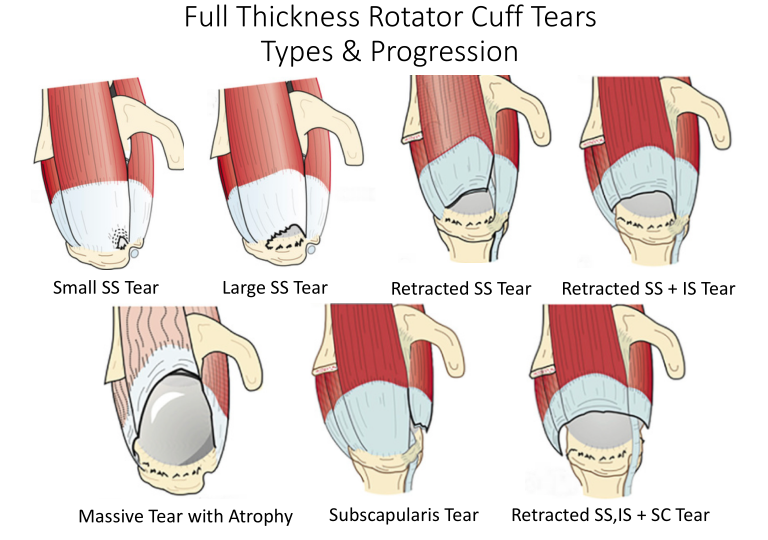

There are many different types of Rotator Cuff Tears and different ways that they can be classified. I prefer to look at Tears in the way that they can be treated. Mr Mullett likes to think of them as either being Acute or Chronic, which Tendons have been Torn, whether they are Partial or Full Thickness Tears, how big they are and whether it will be technically possible to repair them. Other considerations are the quality of the tissue and fatty atrophy, other associated shoulder problems and the age, health and expectations of the individual patient.

- Acute v Chronic Tears – most Rotator Cuff tears are chronic and have slowly developed over time. However, sometimes patients can sustain an acute or an acute-on-chronic tear following a specific injury or event. If in Acute Tear is repaired within 3 – 4 months of its onset, it is likely that it will heal better than if the repaired later. For chronic tears this time window is less important.

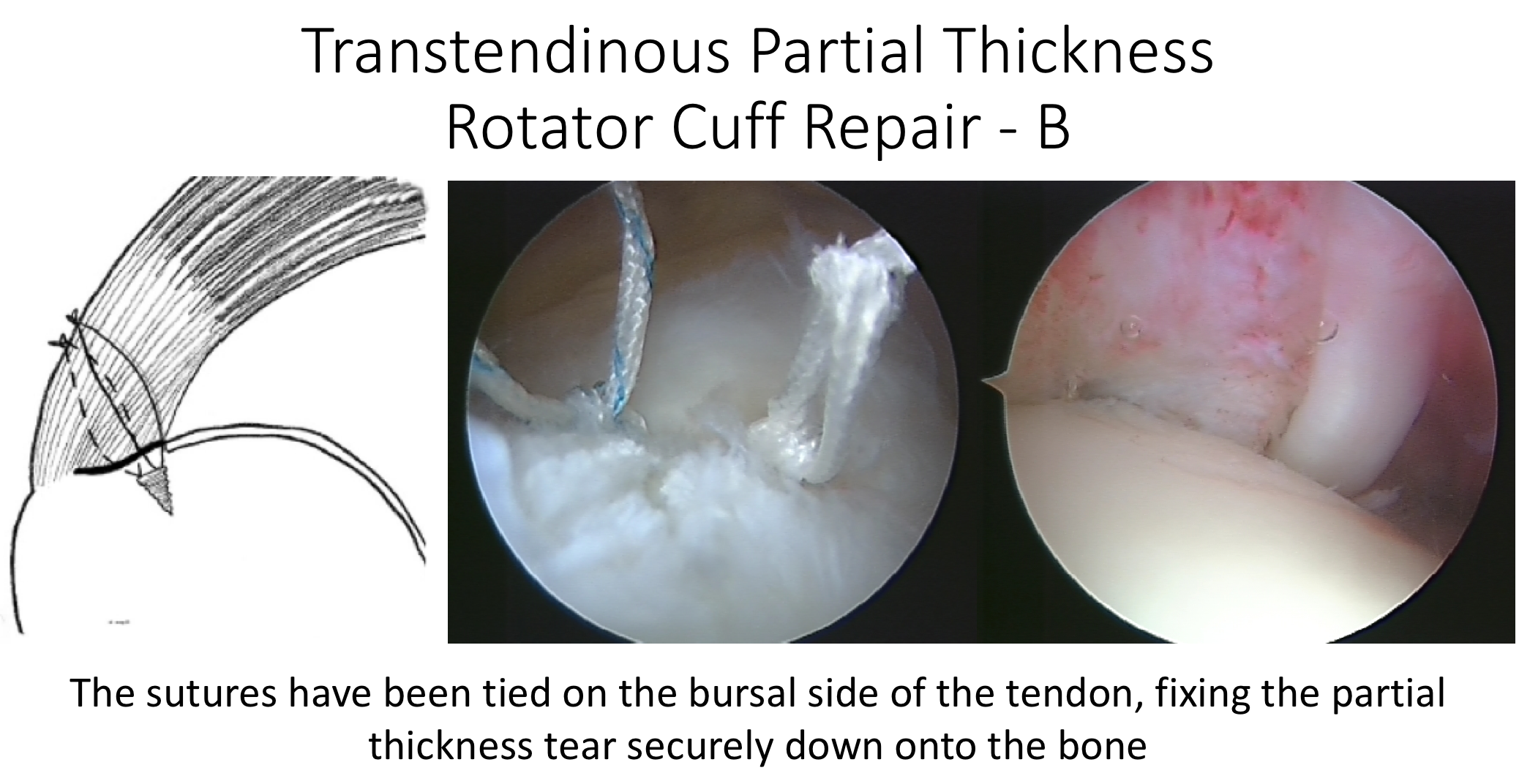

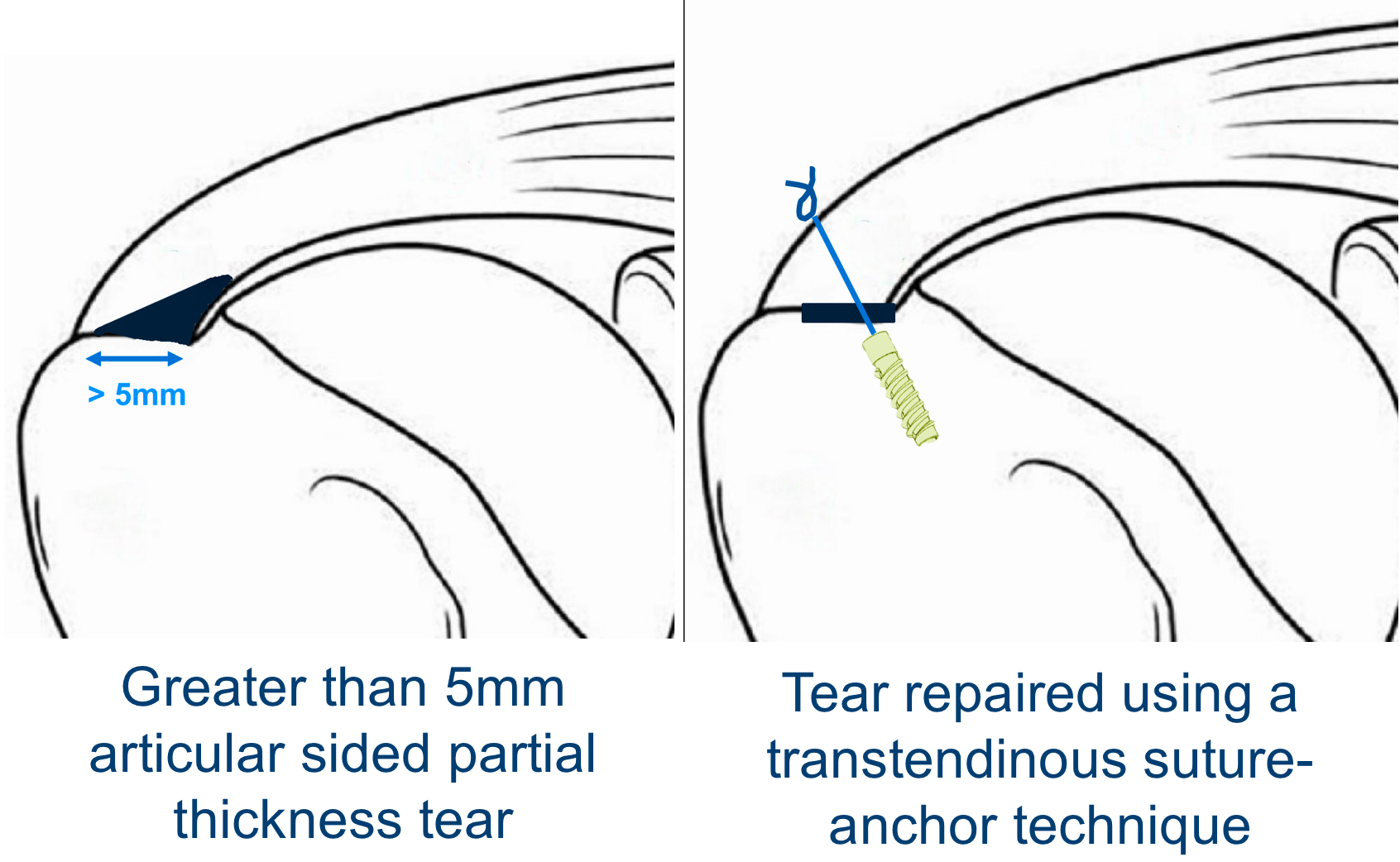

- Partial v Full Thickness Tears – Partial Thickness Tears tend to occur in younger patients and at an earlier stage of Rotator Cuff Disease.

- 80% occur on the articular side of the tendon, which is thought to be the result of a ‘watershed’ in the blood supply to the tendon

- Not all Partial Thickness Tears need to be repaired as they can sometimes heal or may not progress.

- However, as a general rule, the bigger the size of the tear, the younger the age of the patient and the more severe the symptoms are indications to surgically repair the Tendon as the tear is likely to progress over time.

- Full Thickness tears generally will NOT heal and probably, over time, will propagate/spread further. Most symptomatic Full Thickness Tears will usually require a repair to settle the symptoms.

- Size of the Tear – Rotator cuff tears tend to propagate over time.

- Tear size tends to be measured with regards to the distance with which the torn tendon has retracted from its insertion on the greater tuberosity.

- With advances in surgical technique and equipment it is now possible to repair even very large tears. However, there are still some situations where the tear is so massive, the tendon has begun to disappear or is so stuck and retracted that it may not be technically possible to undertake a repair.

Which Tendon is Torn? – Although the Supraspinatus Tendon is the most commonly torn tendon, Infraspinatus and Subscapularis tears can also occur. Sometimes more than one tendon may be torn at the same time. The best way to treat specific tendons and combination tears can differ depending on the tendons involved.

Quality of the Torn Tendon – Rotator Cuff Tears usually occur in degenerate tendons. Sometimes the degeneration / ‘wear-and -ear’ is so advanced that the actual quality of the torn Tendon is not mechanically strong enough to hold a repair and probably will not heal.

Fatty Atrophy – When a Tendon is torn, the muscle that it was connecting to the bone will no longer be able to work and undergoes Disuse Atrophy. If this situation is sustained the muscle cells may then begin to be replaced by fat cells, Fatty Atrophy. Unfortunately, this is an irreversible process and, even if the Tendon is repaired and the muscle re-activated, the muscle cells cannot be restored. If the muscle of a torn tendon has undergone significant Fatty Atrophy, even if the tendon can be technically repaired, it will not regain its function.

Associated Shoulder Problems – Rotator Cuff Tears are often associated with other wear and tear problems in the shoulder. These include Long Head of Biceps Tendonitis, AC Joint problems and Shoulder Joint Osteoarthritis. How significant the Rotator Cuff Tear’s contribution is to a patient’s symptoms, when any of these associated problems are present, may determine how it is best treated.

Age, Health and Patient’s Expectations – Mr Mullett tends to look at age physiologically rather than Chronologically!! That said, younger patients usually have a better healing potential, are more active and will have higher functional expectations. As a result, they are likely to heal better and more quickly following a bigger procedure and may be more tolerant of undergoing a protracted recovery period to gain the best function possible. Older patients and patients with other significant health issues may not heal as well and are only looking for pain relief and a recovery of normal day to day function. They may be less prepared to undergo a ‘heroic’ procedure with a protracted recovery to gain the best function and would prefer a less complex procedure with a quicker recovery of acceptable function.

• As with a Supraspinatus Tendonitis, ‘wear-and-tear’ plays a considerable part in the development of Rotator Cuff Tears and the onset of symptoms can often be quite insidious. As a result, many people find that their symptoms gradually develop over time. In other cases, a specific injury or incident can create a tear or propagate further a chronic tear and spark off a sudden onset of symptoms.

• There is a bulge on the side of the Humeral Head (Greater Tuberosity) where the Supraspinatus and Infraspinatus Tendons insert into the bone. As the shoulder moves, this bulge lies directly under the acromion between 60 and 120 degrees of elevation. This is the point where the space between the top of the Humeral Head and the Acromion is the narrowest. This is known as the ‘Painful Arc’ of movement.

• The early symptoms of a Rotator Cuff Tear tend to be a background pain over the shoulder with particular discomfort when elevating the shoulder within the ‘Painful Arc’ and associated weakness. The shoulder is often uncomfortable to lie on at night.

• As symptoms deteriorate the shoulder becomes increasingly painful all of the time. Pain tends to occur on more directions of movement and the shoulder can appear to become weaker. Night discomfort often becomes more of a feature.

• With chronic shoulder pain, the muscles that help to stabilize the scapula often try to hold the shoulder up, in a more protected position. Overtime these muscles can begin to ache so that the pain can appear to radiate up towards the neck and over the shoulder blade.

• History – Most people notice a gradual onset of pain and discomfort over the top and side of their shoulder. Sometimes people can identify a specific injury or incident that triggered their problem. They may notice particular pain on elevating their arm and in bed at night. As the condition deteriorates, they may get pain more of the time and on more directions of movement. They also might notice some weakness. In extreme cases they may not be able to actively elevate their shoulder at all.

• Examination – Occasionally the patient can experience some discomfort on palpation over the front edge of their Acromion. In the case of longstanding tears the Rotator Cuff muscles may undergo atrophy, which can be seen as ‘wasting’ of the muscles over the shoulder blade (scapula). People may have a ‘painful arc’ on elevating their shoulder and positive ‘impingement signs’. People with Rotator Cuff Disease often have associated problems with Acromioclavicular Joint (ACjt) arthritis and Long Head of Biceps Tendonitis and may have symptoms and signs of these as well.

• Investigations –

o X-Ray – An x-ray does not usually demonstrate the soft-tissues of the Rotator Cuff. However, the shape of the acromion, ACjt osteoarthritis and calcific deposits can sometimes be noted. In extreme cases of longstanding Rotator Cuff Tears the humeral head can be seen to have migrated superiorly under the acromion and even to have developed arthritis (Rotator Cuff Arthropathy)

o Ultrasound Scan (USS) – An USS will nicely demonstrate the Rotator Cuff tendons and the Long Head of Biceps. It is able to show whether there is a tendonitis, partial or full thickness tear of the tendons.

o MRI Scan An MRI scan is the best investigation to visualize the rotator cuff. It can show all of the tendons and whether there is a tendonitis, partial or full thickness tear. It will also demonstrate the acromion and ACjt and their relationship with the tendons. If there has been a longstanding tear the MRI can show evidence of how far the torn tendon has retracted and if there is any evidence of muscle belly atrophy. An MRI scan will also show up any other problems around the shoulder.

Treatment options available

Many patients with a Supraspinatus Tendonitis can be successfully treated non-operatively with a combination of NSAIDs (Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs) , Physiotherapy and use of steroid injections .

• Physiotherapy – Physiotherapy and specific Rotator Cuff Strengthening exercises are the main-stay of the initial treatment for Supraspinatus Tendonitis. By specifically strengthening the Supraspinatus muscle it can work and contract more efficiently pulling the humeral head downwards and allowing the tendon to move more freely. Anti-inflammatory medication can help pain and swelling

• Subacromial Cortisone Injection –

- If patients have had painful impingment for greater then 4-6 weeks a subacromial steroid injection may be helpful.When injected into the Subacromial space it has the potential of settling severe inflammation, allowing the patient to undertake their rehabilitation exercises.

- A Subacromial Cortisone can be easily administered in the Out-Patient Clinic. It is a quick and relatively painless procedure. Afterwards patients can continue with their normal day-to-day activities. Occasionally patients can feel a bit of soreness around their shoulder later that day, but this usually passes fairly quickly.

- It often takes several days before someone notices the benefits following a Cortisone injection and sometimes several weeks. The Cortisone works in the background and there is no specific requirement to particularly rest the shoulder or to do extra exercises. The full benefits of a Cortisone injection are usually felt within a month. In some cases, the Cortisone may not give any benefit, this may be an indication of the severity of the Supraspinatus Tendonitis.

- A Cortisone injection only lasts in the body for a few days. Any benefit that someone gets from the Cortisone will be from its acute anti-inflammatory effect allowing the Supraspinatus Tendonitis to settle. If the symptoms do return after a while, it is not because the Cortisone has worn off, but because the inflammation has returned.

- Infections can occur after any type of injection but are extremely rare (1 in 15,000). If someone feels that they are developing an infection within 48 hours of a Cortisone injection they should seek advice from their Family Practitioner.

• Surgery for Supraspinatus Tendonitis – In some instances a Supraspinatus Tendonitis fails to respond, or continues to recur, despite adequate Physiotherapy and Cortisone treatment. In this situation the only treatment that is likely to settle the symptoms is Surgery.

Arthroscopic Subacromial Decompression

The best operation for someone with a Supraspinatus Tendonitis, that is refractory to treatment, is an Arthroscopic Subacromial Decompression. At the time of the surgery Mr. Mullett will examine the entire joint and then remove bone spurs and inflamed bursa thet are causing pain.

1. An Arthroscopic Subacromial Decompression can usually be done as a Day Case procedure and the patient’s shoulder does not need to be immobilized for anytime afterwards. The surgery aims to remove the part of the Acromion that has been causing the Impingement. It does not specifically deal with the underlying tendonitis. However, by enabling the Supraspinatus Tendon to run freely it allows for the Tendonitis to settle down. As a result it usually takes between 3 – 6 months to gain the full benefits of the procedure. It has a high success rate with around 95% of patients being happy with the result 6 months after their operation. .( see ASD leaflet )

Management of Rotator Cuff Tears

- There is a vast variation between the specific symptoms, types and chronicity of a tear and the needs and expectations of patients who present with a symptomatic Rotator Cuff Tear

- There are also many different ways of treating and repairing Rotator Cuff Tears

- My approach to treating a patient with a symptomatic Rotator Cuff Tear is to assess the specific issues and nature of their problem and to then base my recommendation of how to treat their Rotator Cuff Tear, based on this

Surgery for Rotator Cuff Tears

- I undertake all of my Rotator Cuff Repairs using Arthroscopic Surgery (keyhole surgery)

- The basic aim of any Rotator Cuff Repair is to mobilise and freshen up the ends of the torn tendon, to freshen up the boney insertion on the humerus and then to position and re-attach the tendon back down to its original insertion, achieving a tensionless repair

- To achieve this there are multiple techniques, implants and strategies that can be used

- The descriptions of the procedures outlined below are based on the general technique. The specific details and pros and cons of the various implants and equipment that I use are covered in the Arthroscopic Surgery Section

find out more about Arthroscopic Shoulder Surgery….(Patient Information – Arthroscopic Shoulder Surgery)

Patient Information Leaflet Video

Healing of Rotator Cuff Tears

- Rotator Cuff Tears usually occur in tendons that have undergone ‘wear and tear’ and, as the tear occurs, the degenerate tendon is no longer strong enough to withstand the mechanical forces placed on it

- When a Rotator Cuff Tendon is repaired it is still degenerate and, as a result, its healing potential is not as good as a normal, healthy tendon

- Surgical techniques and implant technology are constantly advancing and we are currently able to mobilise and successfully repair nearly all tendon tears

- However, despite this, a number of repairs still fail to heal

- This is likely to be due to the poor healing potential of degenerate tendons

- The latest advance in Rotator Cuff Repairs, ‘Ortho-Biologics’, involves trying to improve and optimize the healing potential of degenerate tendons

find out more about ‘Ortho-Biologics’….(Patient Information – Arthroscopic Surgery – Orthobiologics)

Factors that May Affect Rotator Cuff Healing

There are a number of factors that have a relative effect on a rotator cuff repair healing and include,

- Age of the patient

- Size of the tear and retraction

- Muscle atrophy

- Chronicity of the tear

- Smoking

What is the Required Rehabilitation?

Post-Operative Guidelines –

Rotator Cuff Repair – Large tears (>3cm)

Mr.Hannan Mullett ,Consultant Shoulder Surgeon

Treatment note: Directly following the repair, integrity relies essentially on the structural construct. The conservative post-operative protocol is characterized by either a delay in the initiating of and / or restriction of passive range of motion (PROM). Remodeling repaired tissue does not reach maximal tensile strength for 12-16 weeks post repair. No formal strengthening should be performed until 12 weeks.

The risk of re-tear is greatest in the first 12 weeks post-surgery. Groups with greater risk of re-tear include older patients, smokers, diabetics, those with minimal postoperative symptoms and those with >3 cm tears.

The risk of stiffness is greatest in younger patients (<50 yrs.), those with PASTA type rotator cuff tears (Partial articular supraspinatus tension avulsion), those having an associated labral repair and single tendon repairs.

Timescales are guidelines and are dependent on individual factors and pre-operative status. Factors that may affect progression rate:

- Pre-operative stiffness

- Age

- Tissue quality

- Associated procedures

Acute protective phase (0-6 weeks)

Histology

Peak collagen deposition and growth factors 10 days post op with plateau at 28-56 days. Requires gentle stress to guide fibre orientation but no strain by limiting active motion.

Goals

- Patient education

- Protect surgical repair and optimize tissue healing

- Diminish pain and inflammation

- Prevent post-operative adhesions 5. Minimise muscle inhibition

Immobilisation

- Patients generally wear a sling for 6 weeks for comfort and to avoid stressing the repair. The sling is removed to allow axillary hygiene and when patient is performing their exercises

Rehabilitation

- Avoid active assisted or passive mobilization past 80° elevation in scapula plane, 50% of ER (compared to opposite side) respecting pain and movement pattern.

- Cryotherapy as needed

- Elbow, wrist and hand exercises.

- Simple scapula exercises e.g. shoulder shrug

- Active assisted / supported movement within the safe zone and limits of pain

- Encourage use of hand in sling for light unloaded, pain-free activities. Patients that use the hand of the operated arm during the immobilization phase have better outcomes in terms of pain and function.

- Closed kinetic chain exercises

- low load on the shoulder and ensuring congruency scapula on thorax; e.g. table slides, walking away from the table.

- Submaximal isometrics (<30% MVC) rotator cuff

- Active scapula exercises e.g. shoulder shrug

Intermediate phase (6-12 weeks)

Histology

Inflammatory and repair phase has passed and healing progressed to remodelling phase. The application of low-level force during this time frame aids in orientation of fibres within collagen matrix and enhances tensile strength of repair.

Goals

- Preserve integrity of repair.

- Improve functional range of movement including full elevation

- Re-educate cuff recruitment and scapula control through range

- Improve neuromuscular control by re-educating sensorimotor / proprioceptive function

- Emphasize normal patterns of movement

Rehabilitation

- Avoid forced passive stretching into combined abduction / external rotation. Active movement into this position is allowed as long as pain free and good control.

- Avoid forced end range stretches / mobilization especially ER with arm by side

- Avoid lifting / loading until 12 weeks

- Avoid weightbearing through operated arm e.g. getting out of a chair

- Avoid force hand behind back / extension

- Gentle mobilization of capsular restriction if necessary (respect restrictions)

- Progress cuff and scapula recruitment through range. Any exercise prescription should emphasis on good cuff and scapula control. Active assisted exercises progressing to active exercises-utilise short lever, supine and closed kinetic chain. Avoid long lever open chain exercises until 12 weeks

- Progress kinetic chain integration

- Increase function, emphasis on correct movement pattern

- Closed kinetic chain work to enhance co-contraction

Late stage (12 weeks to 6 months)

Histology

Tendon to bone healing should be able to endure the initiation of strengthening exercises. However, the addition of specific strengthening should be guided by preoperative findings in terms of tissue quality, patient age and whether primary or revision surgery. Careful progression of loading is essential to avoid compromise to the repair.

Goals

- Restore full active range of movement

- Establish optimal neuromuscular control

- Restore optimal cuff and scapula control through range and under load

- Optimise functional upper limb strength and endurance

- Return to full work / sport and recreational activities

Rehabilitation

- Regain optimal range of motion including combined positions

- Strengthening and endurance exercises for rotator cuff and scapular stabilisers

- Enhance neuromuscular control through range

- Closed kinetic chain exercises with increased load

- Functional strengthening and endurance exercises

Phase 4 – advanced strengthening (6 months +)

Histology

Remodeling phase is close to completion at 4 months and the repaired rotator cuff tissue is relatively mature, therefore able to withstand greater stresses.

Goal

Patients returning to sport or with high functional demands may require more advanced strengthening to ensure they regain maximal tensile strength and functional endurance.

Rehabilitation

- Progression of strength training with optimal control and movement pattern

- Sport specific training

- Endurance training

- Promote concept of prevention

Functional Milestones

- Driving -depends on side and whether automatic generally after 8 weeks when patient has adequate control

- Swimming 16 weeks

- Golf 16 weeks

Reference

Oliver A van der Meijden et al (2012) Rehabilitation after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: Current concepts review and evidence-based guidelines.

International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy 7(2): 197-218

Detailed Anatomy of the shoulder

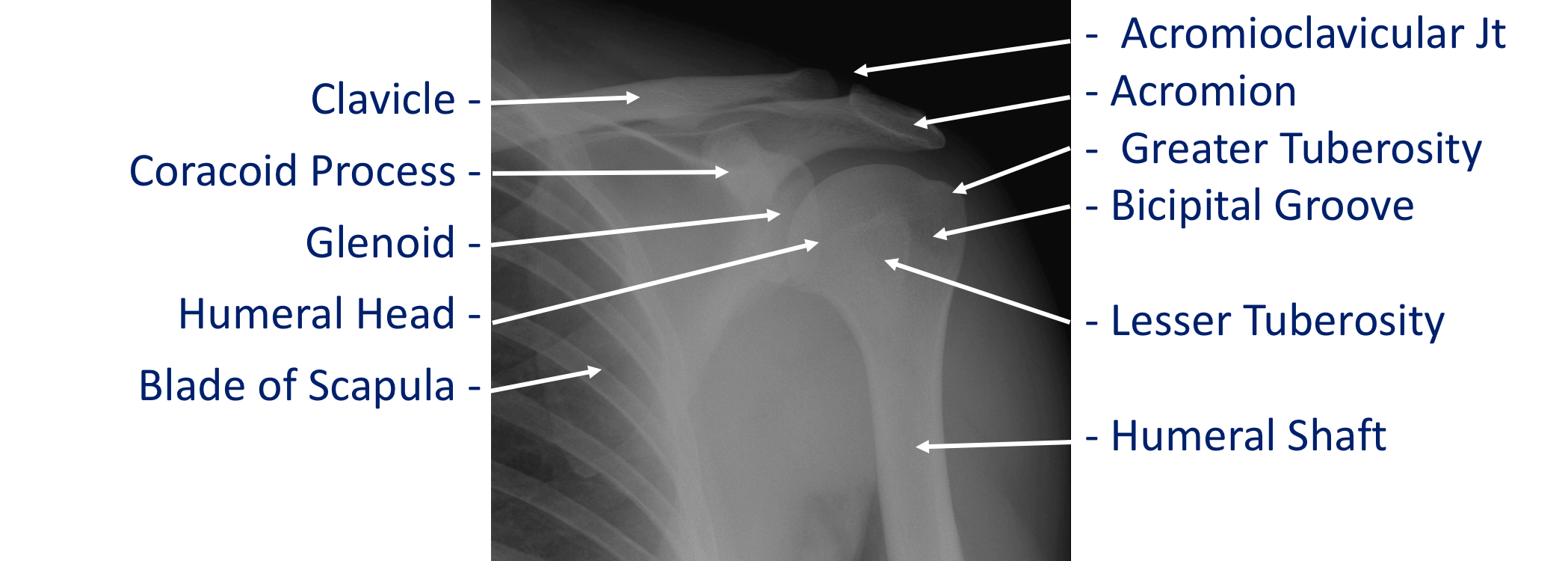

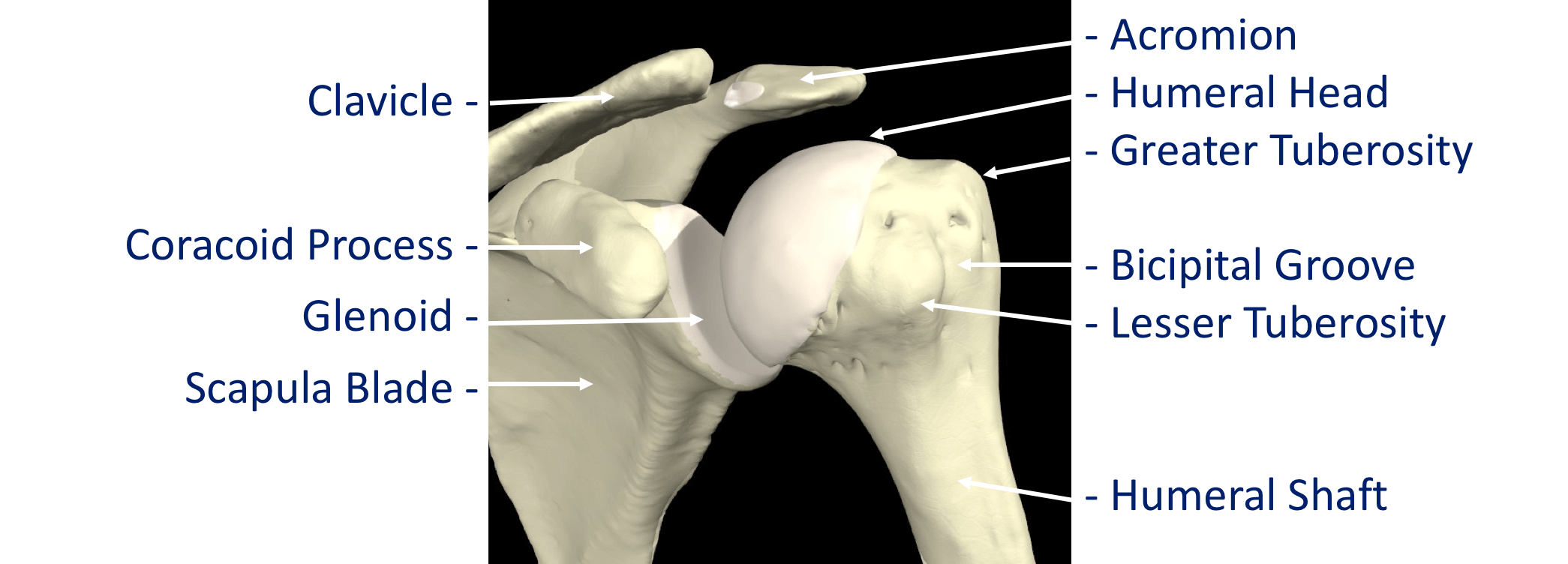

The shoulder is made of up 3 bones that interact together to for a supporting structure for the upper limb. We refer to this grouping of bones as “the shoulder girdle”. The bones of the shoulder girdle are;

- The Humerus – the upper arm bone with the ‘humeral head’ (the ball of the shoulder joint) on the top end

- The Scapula – the shoulder blade. There a number of parts to the scapula.

- the ‘glenoid’ (the socket of the shoulder joint)

- the ‘acromion’ (which covers the top of the glenohumeral joint and attaches the scapula to the clavicle)

- the ‘coracoid’ (a bony ridge at the front of the scapular to which a number of ligaments and muscles attach)

- The Clavicle – the collar bone which connects the acromion part of the scapula to the sternum (the breast bone) ‘strutting’ the shoulder out. This is the only direct bone connection that the shoulder girdle has with the rest of the skeleton.

Where a bone come into contact with another is known as a joint. The joints of the shoulder are;

- The Glenohumeral Joint – formed between the humeral head (ball) and the glenoid (socket).

- The Acromioclavicular Joint – the joint that connects the scapula to the outer end of the clavicle

- The Sternoclavicular Joint- the joint that connects the inner end of the clavicle to sternum. This is the only bony connection between the ‘shoulder girdle’ and the main the skeleton

- The Scapulothoracic Joint – this joint involves the movement of the scapula over the ribs at the back of the chest. This is a ‘psuedo’ joint (not a real joint as it does not have any articular cartilage.

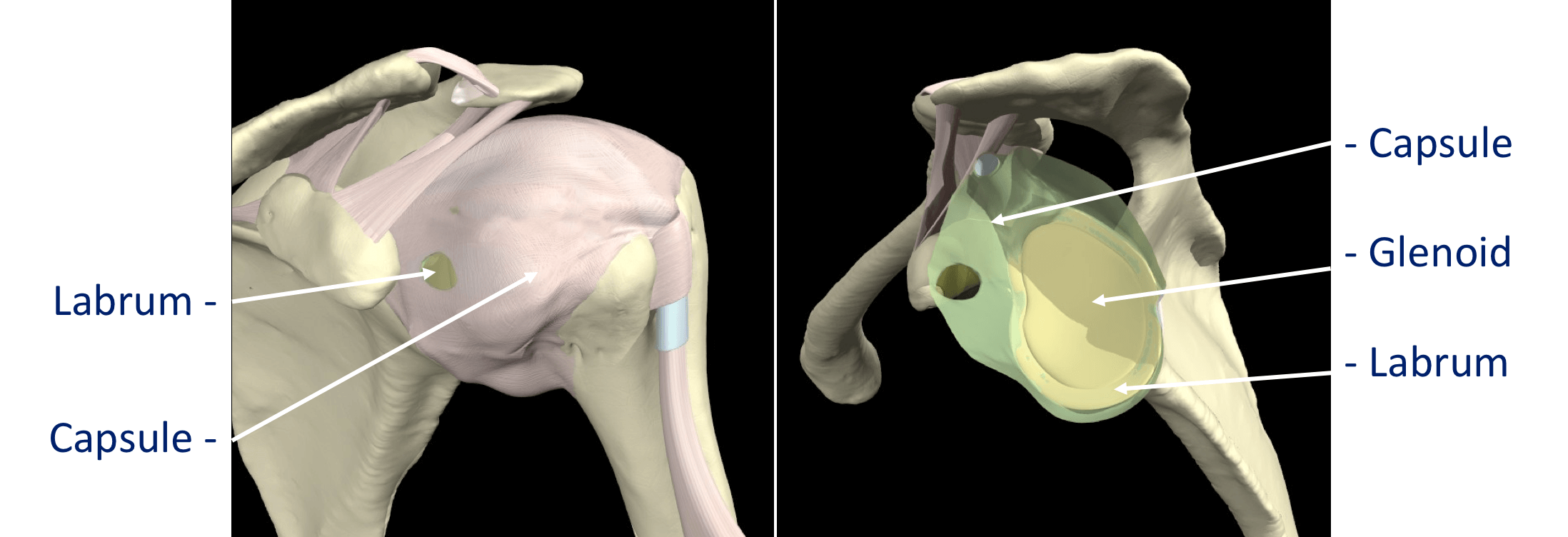

The tissue components within the Shoulder Joint itself;

- The Glenoid Labrum – this is a ‘rim’ of tissue that goes around the outer edge of the glenoid, the tendon of the long head of biceps attaches to the top part of the labrum. The labrum effectively deepens the glenoid socket which helps to increase the stability of the humeral head. It works a bit like a ‘chock’ under a wheel preventing the head from ‘rolling’ over the edge.

- The Joint Capsule – this is a watertight sac that surrounds the joint. It is formed circumferentially from around the base of the glenoid socket and passes outwards to join circumferentially around the neck of the humeral head. The inner lining of the sac is covered with synovial tissue which produces synovial fluid that lubricates the joint and provides joint nutrition.

The bones and joint of the shoulder are held in position by strips of very strong tissue, known as ligaments. They attach bone to bone where as a tendon attaches muscle to bone. The main ligaments of the shoulder girdle are:

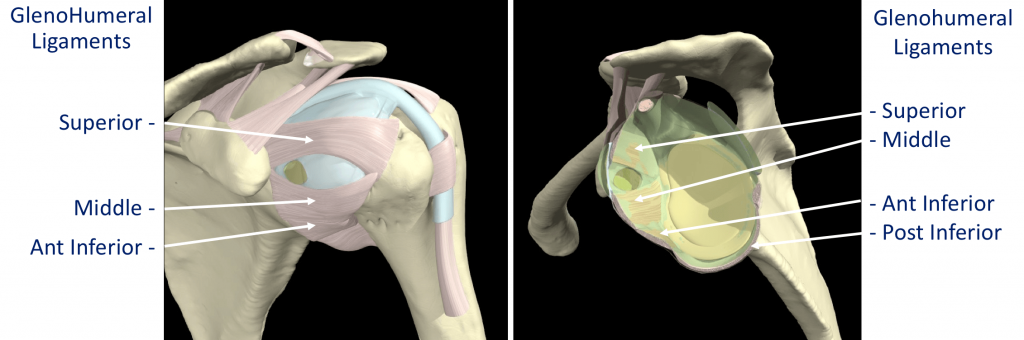

- The Glenohumeral Ligaments (GHL)– within the joint capsule there are 4 strong ligaments that connect the glenoid to the humerus. These are the main structures that keep the shoulder in place and stop it from dislocating. There are 3 ligaments at the front (Superior, Middle & Anterior Inferior Glenohumeral Ligaments) and 1 ligament at the back of the joint (Posterior Inferior Glenohumeral Ligament).

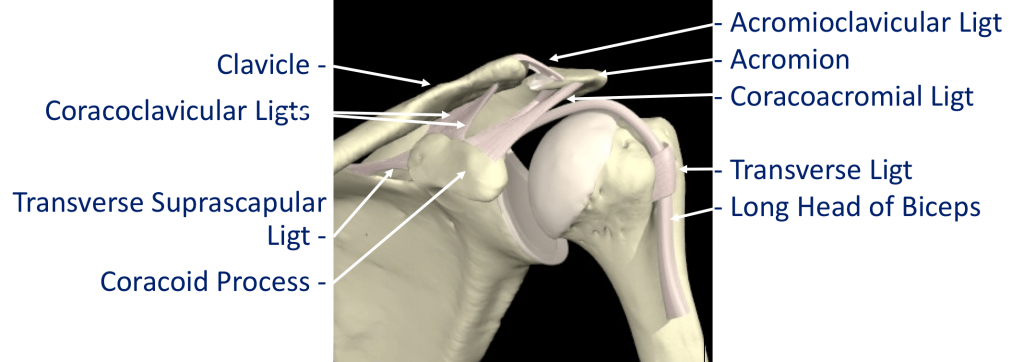

- The CoracoAcromial Ligament (CAL) – this ligament connects the acromion to the coracoid forming a tunnel. The Rotator Cuff tendons pass under this tunnel. In some circumstances the tip of the acromion and the ligament can thicken and cause Impingement to the tendons as they run underneath

- The Acromioclavicular Ligaments (ACL) – these are short ligaments that attach the clavicle to the acromion within the acromioclavicular joint (AC jt)

- The Coracoclavicular Ligaments (CCL) – these are 2 ligaments that connect the clavicle to the coracoid. They help to supply additional stability to the clavicle and the ACjt.

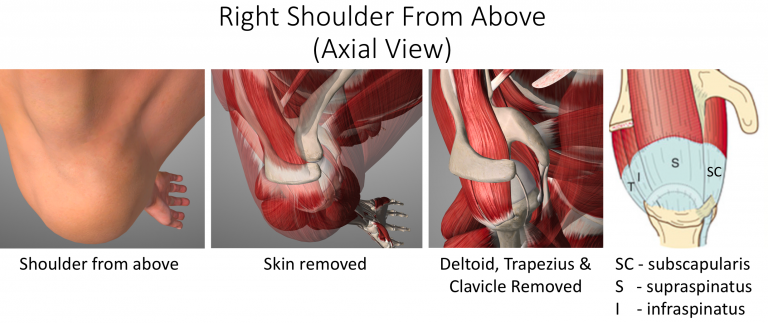

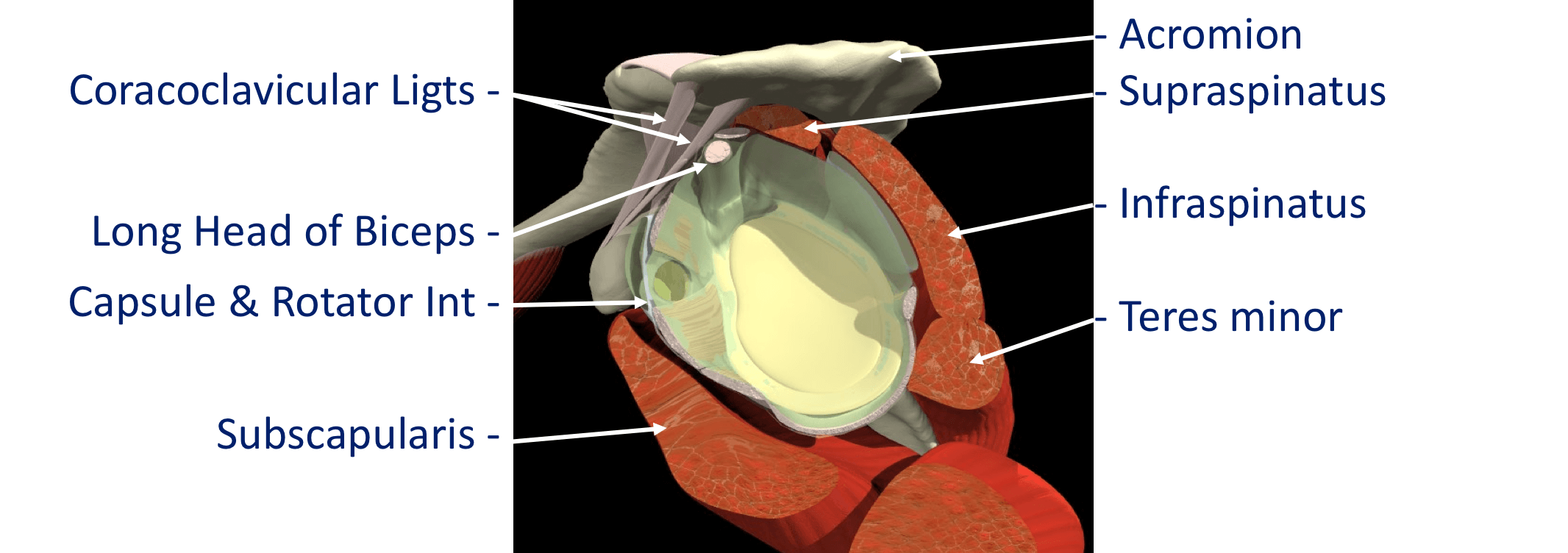

The Rotator Cuff

This refers to a group of muscles that hold the head of the upper arm into the socket of the shoulder. These muscles all insert into the bone as tendons so we often refer to the structure as the rotator cuff tendons. This layer lies on top of the bones and connective tissue.

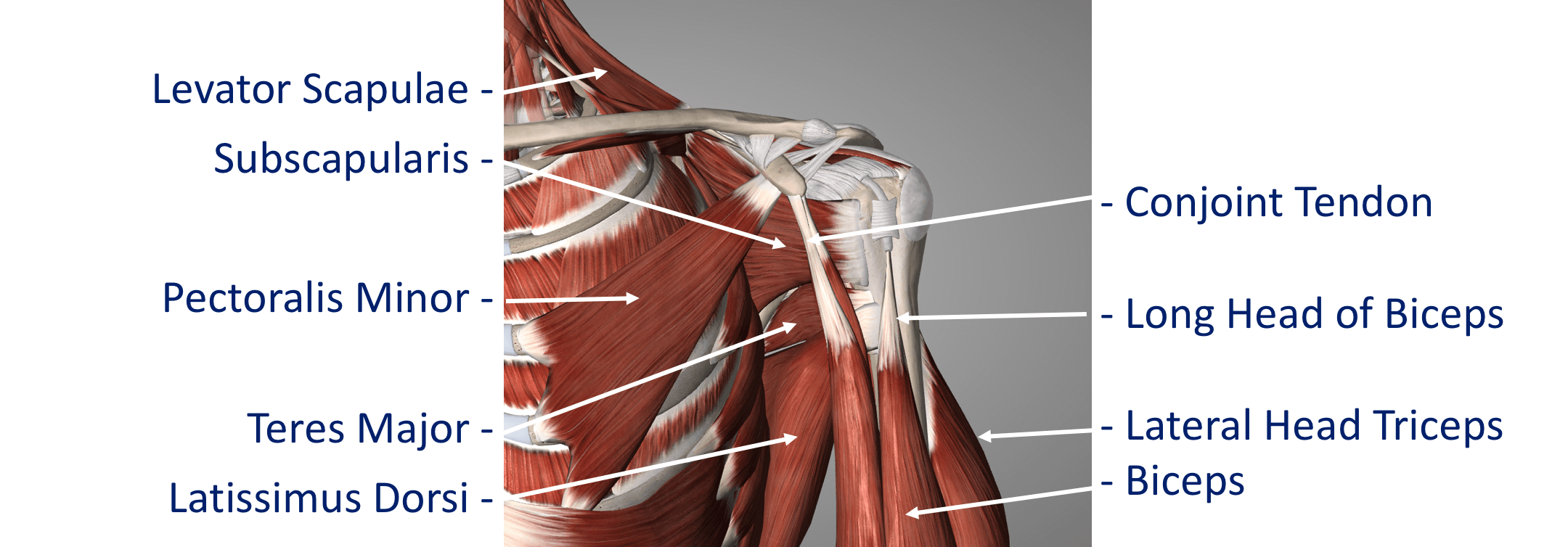

The Rotator Cuff Tendons – this is formed by a group of 4 tendons that connect the deepest layer of 4 muscles to the humerus. These muscles are,

- Subscapularis

- Supraspinatus

- Infraspinatus

- Teres Minor

The muscles surround the shoulder and as their 4 tendons pass over the joint they converge together. As these bands of tissue attach onto the humerus they blend together and form a ‘tendon cuff’. This is known as the Rotator Cuff

The Biceps Tendon – the Biceps muscle, on the front of the arm, is formed from 2 tendons; the long head and short head. The Long Head of Biceps tendon begins at the top of the glenoid (with the labrum) and passes out through the shoulder joint to connect to the biceps muscle. The Rotator Cuff tendons and the Long Head of Biceps tendon are positioned very close to each other and are often both affected by injury at the same time. The Rotator Cuff tendons pass underneath the acromion through the Subacromial Space as they insert into the humerus (Fig 9). The narrow ‘clearance space’ underneath the acromion is the commonest place for Rotator Cuff problems to occur.

Additional supporting muscles

There are a large number of muscles around the shoulder which are responsible for moving, stabilising and supporting the shoulder girdle. The muscles can be divided into 4 groups.

Deep Muscles (Intrinsic / Rotator Cuff Muscles) – these are the 4 muscles mentioned earlier whose tendons form the rotator cuff. The muscles all arise from the blade (flat surface) of the scapula and pass over the shoulder joint with the tendons attaching onto the humerus.

- Subscapularis

- Supraspinatus

- Infraspinatus

Teres Minor These muscles often function as a group and are involved in raising, rotating and moving the shoulder in many directions. The combined pull of the Rotator Cuff muscles also pulls the humeral head into the socket of the glenoid helping to stabilise the glenohumeral joint.

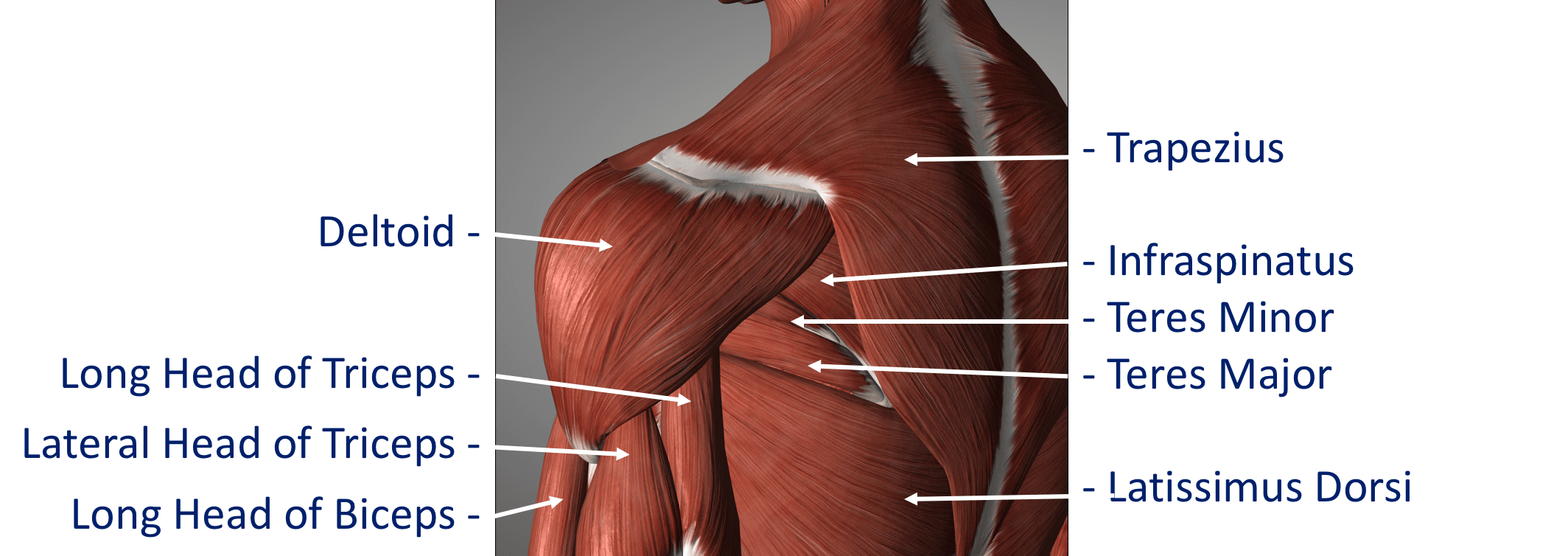

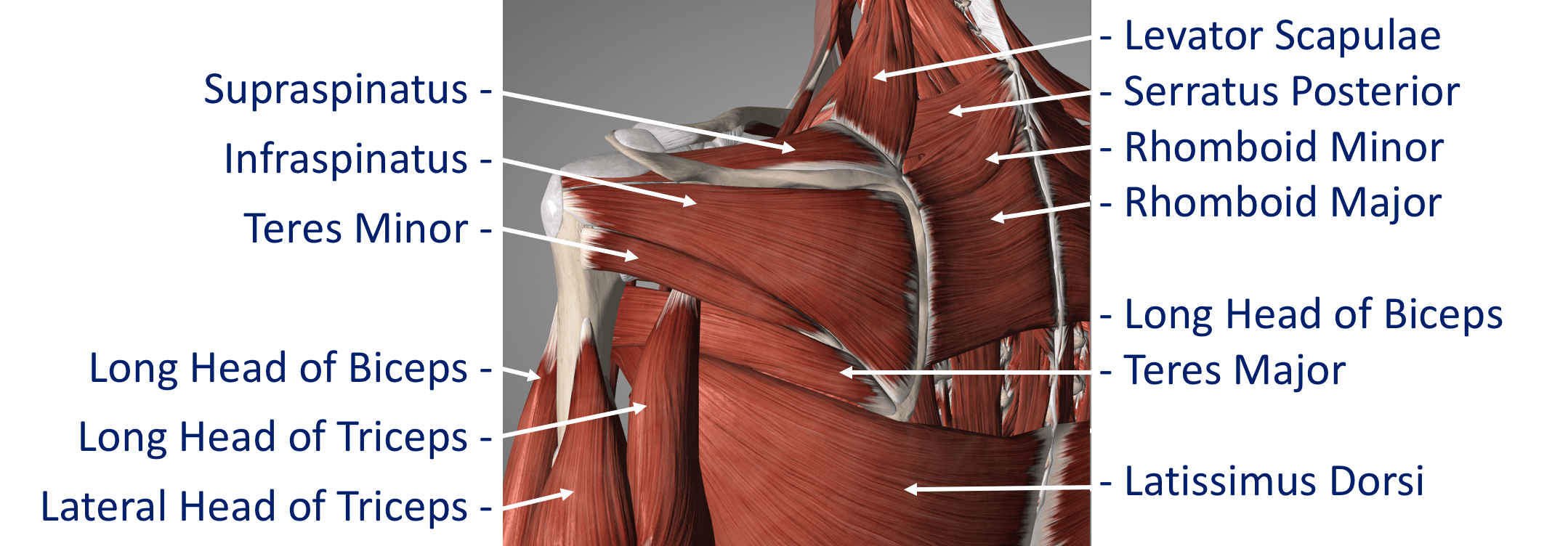

Intermediate Muscles – These muscles provide additional stability and strength to the glenohumeral joint and the shoulder girdle.

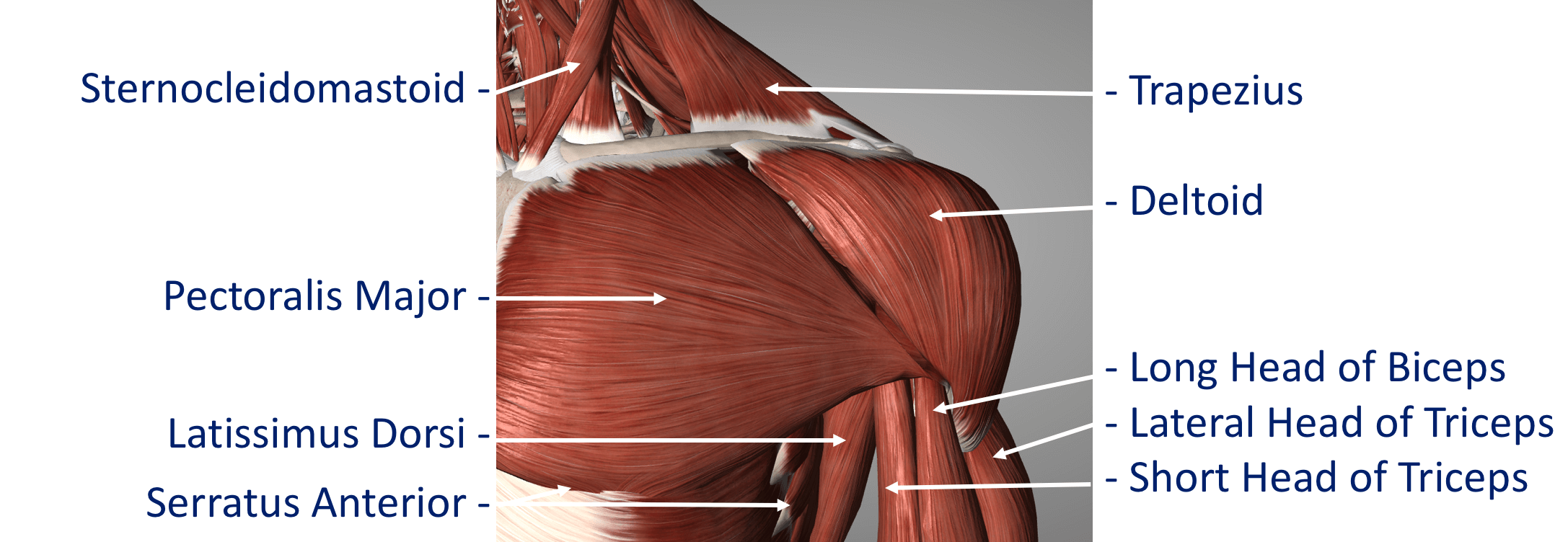

Superficial Muscles (Extrinsic) – These are the large muscles that can be seen around the shoulder externally and provide strength and powerful movements. • Deltoid – this is the large muscle over the top and the front of the shoulder which provides the power to lift the shoulder after the rotator cuff muscles have begun the movement

Pectoralis Major – this is the large muscle over the front of the chest.

Biceps – this is the powerful muscle over the front of the upper arm that flexes the elbow. One of the Biceps tendons (the Long Head) arise from within the shoulder joint. Problems can occur with the stability of the Shoulder if the sequential rhythm in which these muscles contract to move the shoulder is disturbed

Back Muscles (Posterior) – these muscles are involved in suspending the scapula onto the back of the chest wall, stabilising the scapula and moving the scapula over the chest wall (scapulothoracic joint). A number of these muscles, including trapezius, levator scapulae and the rhomboids, originate from the vertebrae of the cervical and thoracic spine. Problems can occur with the smooth movement of the scapula over the chest wall if these muscles are weakened or are not working properly.